I've seen many comparisons of Rails with Django, its Python counterpart.

The Application

I decided to use Django to write a local history application: the story of Snape in East Sussex.

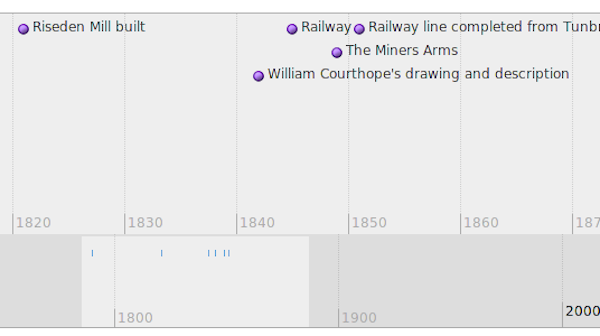

The public timeline

The front and of the application uses a SIMILE timeline to display dates.

First Impressions about Django

Apps

The main thing I was looking forward to while writing the app was modularity. In fact, in the and I made two apps: the specific Snape application and a generic timeline app.

Creating the Database

In Rails, you launch script/generate Model and you obtain a database and a series of migrations, which form a chronology of development of the database.

In Django, you describe the database fields in your model.py file and the run manage.py syncdb.

The advantage of the Django system is that the model holds authoritative information about the fields in the database.

The great disadvantage is that there are no TABLE ALTERing migrations - you have to dump the table creation SQL and manually construct and run TABLE ALTER commands.

Settings

Django's settings file (settings.py) more or less has to be site specific. So that means you have to decide what to check in to your version control system. Some people seem to use a settings.py.default which they then copy to settings.py and alter to the needs of a specific machine.

I chose to keep site specific stuff in a set of JSON files, named after the local machine (see http://gnuvince.wordpress.com/2007/03/15/local-settings-in-django/). It woks quite well, but in Rails as I commonly have a single development machine and a single production one, I am able to avoid the whole problem thanks to config/environments/[development|production].rb.

Static Content

There is a difference between how one handles static files in development and production. Most people seem to use a hack in the urls.py file, indicating where to get static content if in DEBUG mode, whereas in production mode you are supposed to set up Apache aliases for the various directories.

The logic here is that Django should not get involved in serving static content (quite rightly), but it certainly makes setup more laborious. One can achieve a happy medium in Rails using X-SendFile - Rails gets the request and then punts serving to Apache.

Generating URLs

There is an equivalent to Rails' url_for which is available inside Django templates, it's the filter { % url %}. Unfortunately, the first time I wanted to create a URL was actually in Python code - I wanted to redirect. I was unable to find a way to use url from Python code. There is get_absolute_url, which can be implemented inside the model, but it's only for instances.

Overall

I think Django is fairly straightforward for the Rails programmer. The fact that you get a 'free' admin backend (similar to ActiveScaffold), is certainly handy. There are a lot of sources of online information and tutorials, so it's quite easy to get up and running. The main impression I got was of a small framework - while Rails covers a great range of functionality, I felt I came up against Django limitations rather quickly. That may be due to not looking in the right places, but my Google searches showed that a lot of other people were asking the same questions.